Contents

Introduction & The GRACE 3 Guidelines

Timing, Triggers & Associated Symptoms

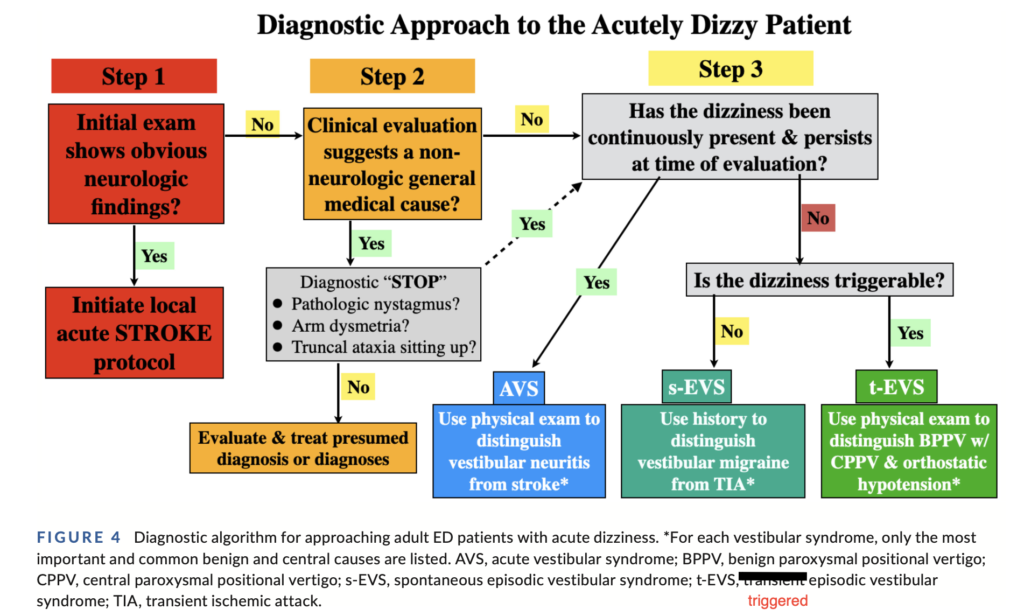

GRACE 3 Approach to the Acutely Dizzy Patient

- Step 1 – Any Neurological Red Flags?

- Step 2 – Obvious Medical Cause?

- Step 3 – Vestibular Syndrome Present?

Vestibular Syndromes

- Triggered Episodic Vestibular Syndrome (t-EVS)

- Acute Vestibular Syndrome (AVS)

- Spontaneous Episodic Vestibular Syndrome (s-EVS)

Nystagmus in Acutely Dizzy Patients

Introduction & The GRACE 3 Guidelines

The Acute dizzy patient is not typically a favourite patient for emergency clinicians to assess due to the wide variety of diagnoses to consider and potential pitfalls. Fortunately, improving evidence and guidelines in this area now allows emergency clinicians to approach such patients with far more confidence in their diagnostic abilities.

In 2023, the release of the GRACE 3 Guidelines – Guidelines for Reasonable and Appropriate Care in the ED: Acute dizziness and vertigo in the emergency department – represents a major contribution to this space [see References & Resources for access to this guideline]

This article will present an approach to the acutely dizzy patient with particular focus on the 3 main vestibular syndromes, combining key features of GRACE 3 and other resources as well as describing one key criticism of GRACE 3 (regarding its definition of Acute Vestibular Syndrome).

Timing , Triggers & Associated Symptoms

The traditional approach to dizziness has been to try to have the patient describe the quality of the dizzy feeling they are experiencing in order to be able to place the patient within a diagnostic category. Qualities such as “presyncopal/fainting feeling”, “vertigo”, “general lightheaded/floaty” feeling or “disequilibrium” (balance problem) are often sought. However the evidence is not supportive of this being particularly useful at helping us determine the eventual diagnosis and patients often have substantial difficulty describing this quality. While typically the dizziness associated with peripheral vestibular disorders or central disorders such as posterior stroke is described as vertigo (a spinning or similar movement sensation), unfortunately sometimes the patient does not describe it this way.

Consequently GRACE 3 focusses on simply “dizziness” and approaches the diagnosis based on the timing, triggers and associated symptoms rather than the quality of dizziness described by the patient.

[Back to Top]

GRACE 3 Approach to the Acutely Dizzy Patient

[Back to Top]

Step 1 – Any obvious neurological red flags?

Key Assessment Features – new onset:

- Significant Headache or Neck Pain

- Motor or sensory changes (especially of face or upper limbs)

- 5 Deadly Ds

-

- Diplopia (vision – double vision)

- Dysarthria (speech)

- Dysphagia (swallow)

- Dysphonia (voice)

- Dysmetria (coordination)

-

Requires general neurological examination including

- Cranial nerves including detecting spontaneous nystagmus at rest (when head still)

- Cerebellar/coordination examination including observing for truncal or severe gait ataxia (inability to walk unaided)

If red flags present –> investigate for central neurological causes. This may require activating an urgent “code stroke” protocol depending on the time window and setting.

Look for spontaneous nystagmus – if present:

- Vertical, isolated torsional (with no horizontal component) or vertical-torsional combined represent red flags for central causes (high specificity, low sensitivity) – do not proceed to Step 2.

- Horizontal or horizontal-torsional spontaneous nystagmus is not a red flag for central causes – so proceed to Step 2 (and then likely onto assessing for AVS in Step 3)

Note the urgency of assessing the neurological exam will depend on the context of the assessment, type of hospital and time window of presentation.

For example, if urgent intervention for stroke is an option (clot retrieval or thrombolysis), then a brief rapid neurological exam (e.g. a “triage exam”) should be performed to determine if a “stroke call” is required for urgent imaging and involvement of a stroke team.

If a stroke call is not required, then depending on patient location and competing department needs, the more complete neurological exam can be completed as required either immediately or in a delayed fashion as part of Step 2 general medical assessment.

About 1 in 10 ED patients with dizziness will have neurological aetiologies (of which 1/3 of these are cerebrovascular).

[Back to Top]

Step 2 – Obvious Medical Cause?

- Does clinical evaluation suggest an obvious medical cause e.g. toxicological (medication toxicity/interaction/overdose), hypovolaemia, acute infection, cardiac arrhythmia?

- The key history of associated symptoms will usually point to a medical cause e.g. change in medication or drug use, bleeding such as GI bleeding, dehydrating illness (e.g. gastroenteritis), fever/chills/infective symptoms, palpitations/shortness of breath/chest pain, altered mental state/confusion.

- Approximately half of ED patients with dizziness have various medical conditions as its likely cause and these will usually be revealed based on history, examination and bedside tests (e.g. urinalysis, ECG, BSL, VBG) +/- other investigations as suggested by the assessment.

- If a medical cause is likely and there are no neurological red flags, including pathologic nystagmus or concerning ataxia (see section below) then investigate and treat for the medical cause.

- Otherwise proceed to Step 3

[Back to Top]

Step 3 – Vestibular Syndrome Present?

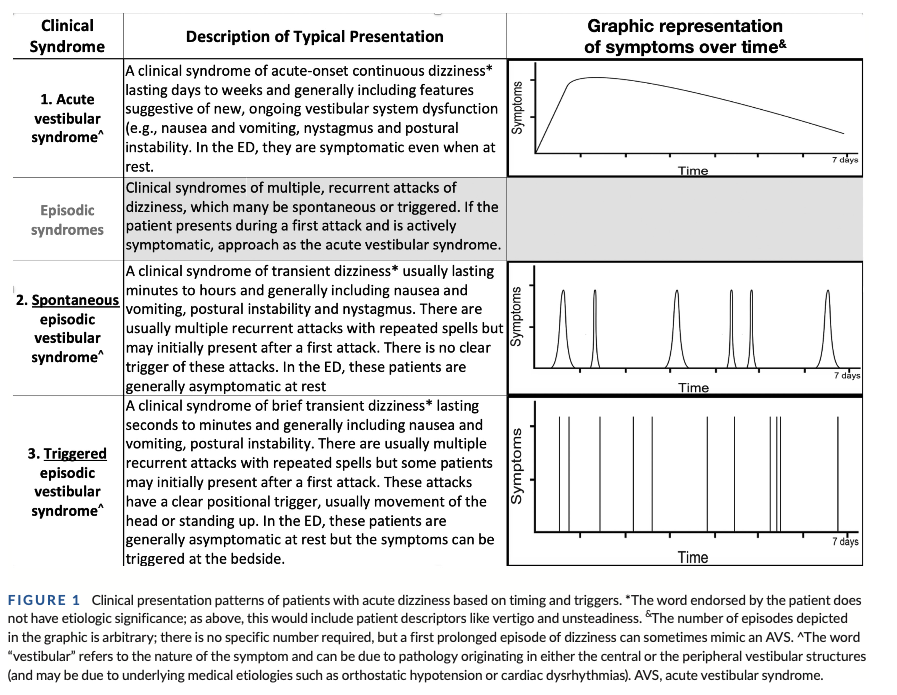

If there are no neurological red flags for a central cause and no obvious medical cause, Step 3 involves categorising the presentation into one of 3 key types of vestibular syndrome which are present in about 1/3 of patients presenting to the ED with acute dizziness. Note “the word “vestibular” refers to the nature of the symptoms and can be due to pathology originating in either the central or peripheral vestibular structures (and may be due to underlying medical aetiologies such as orthostatic hypotension or cardiac dysrhythmias)” [GRACE 3 quote]. In this context, vestibular symptoms refer to acute onset dizziness (usually but not always a “vertigo” sensation) associated with postural instability, nausea and/or vomiting and generally nystagmus (spontaneous or evoked by diagnostic testing).

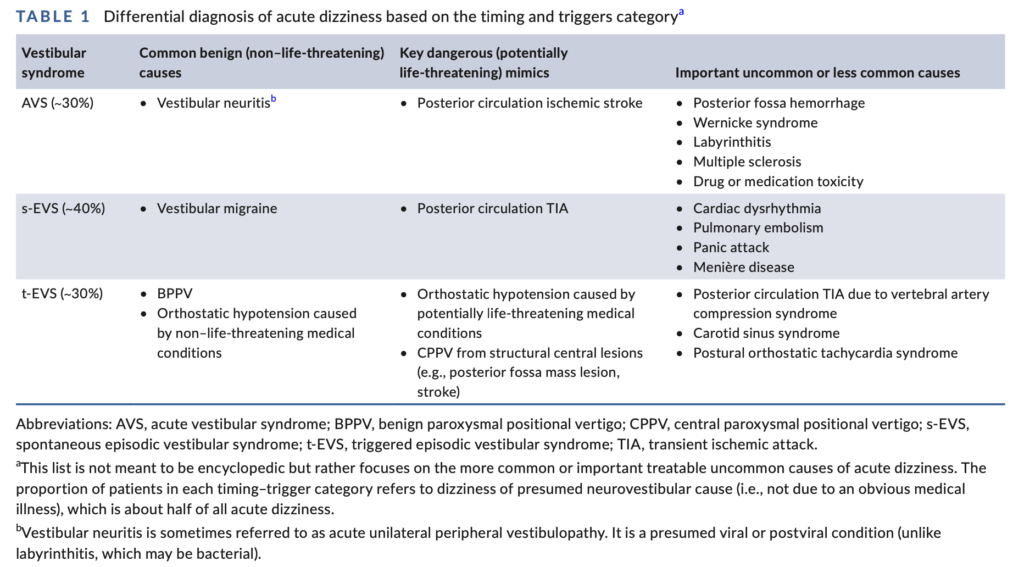

Figure 1 and Table 1 from GRACE 3 describe these vestibular syndromes and their differentials.

[Back to Top]

Figure 1 from GRACE 3 below defines these 3 vestibular syndromes with a graphic representation of how the symptoms present over time.

Table 1 from GRACE 3 below describes the common, dangerous and less common differential diagnoses for each of these 3 vestibular syndromes

[Back to Top]

Triggered Episodic Vestibular Syndrome (t-EVS)

This is the most common presentation of vestibular symptoms in the ED with AVS less common and s-EVS even less prevalent.

Figure 1 from GRACE 3, defines this syndrome. The key features are that it is a transient set of vestibular symptoms (dizziness, nausea/vomiting and postural instability) that are clearly triggered by an event, such as head movement, and that the symptoms soon resolve when the patient keeps still. One aspect that can mislead clinicians, is the observation that with AVS (peripheral or central cause), the vestibular symptoms are often exacerbated by head movements. However, with AVS, the symptoms are still present and continuous even without the head movement trigger and after the exacerbation by head movement, the symptoms will return back to a baseline of persistent dizziness despite the person keeping their head still.

So the key differentiating feature of t-EVS is not just the triggered nature of the vestibular symptoms, but the fact that they resolve when they keep their head still. There is a small cohort of t-EVS patients with just a very mild sensation of non-specific dizziness at all times (see discussion of pseudo-AVS in AVS section below) but their key vestibular symptoms (the more severe dizzy or vertigo symptoms, nausea/vomiting and postural instability) will resolve with keeping their head still.

The most common cause of t-EVS is BPPV (Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo) due to the presence of a cannalith (tiny stone) in a unilateral semi-circular canal within the inner ear vestibular apparatus. The tests and treatments will now be discussed but note that the demonstration videos are provided at the end of this section.

Diagnosing BPPV and the affected semi-circular canal

The most frequent semicircular canal involved (approx 70-80%) is the posterior canal so test for this first using the Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre (to learn see “BPPV Videos” below).

- A positive test, triggered by the head movement of the Dix-Hallpike test, demonstrates characteristic nystagmus that is:

- Latent – starts after an initial delay period of several seconds (allegedly can be as long up to 20 seconds). The nystagmus is usually accompanied by the recurrence of their dizzy, generally vertiginous, symptoms.

- Transient – gradually resolves over usually 15-30 seconds.

- Typical in direction – the nystagmus from posterior canal BPPV is classically upbeat torsional (so combined vertical upbeat and torsional). Interestingly if the patient looks towards their downward ear it can appear more torsional and if they look towards their upwards ear it can appear more vertical upbeat. Note these nystagmus directions are not in any way concerning for a central cause because they occur as expected with head movement rather than spontaneously.

- The Dix-Hallpike test should only be positive with characteristic nystagmus when testing one side – left or right.

- If there is either no nystagmus seen when testing both left and right sides, or it is actually horizontal nystagmus, next test for “lateral canal” BPPV, (aka “horizontal canal”, accounting for 15-30% of BPPV) using the Supine Roll test (to learn see BPPV videos below). If positive, the nystagmus will be horizontal and usually will beat towards the ground when testing both left and right sides (known as geotropic lateral canal BPPV). Uncommonly it will be horizontal but beat away from the ground on both sides (known as apogeotropic lateral canal BPPV).

- Anterior canal BPPV is a rare presentation of BPPV (3% of cases). It presents with bilateral downbeat nystagmus when doing the Dix-Hallpike test.

Where the patient is negative on both Dix-Hallpike and Spine Roll tests:

- Ensure the tests have been performed correctly – review the instructional videos to optimise technique.

- Consider whether these are false negative tests, if the symptoms had already resolved prior to examination

- If the symptoms are triggered by standing but not head movement per se, consider Orthostatic hypotension.

- Consider other differentials of t-EVS (e.g. in Table 1 above).

- Consider referral to a physio with vestibular training for re-review if the history is strongly suggestive of BPPV despite negative tests.

Treatment

If the Dix-Hallpike test is unilaterally positive for posterior canal-BPPV it should then be treated with a cannalith repositioning manoeuvre such as the Epley Manoeuvre (to learn see “BPPV Videos” below), starting on the same side (left or right) that was positive with the Dix-Hallpike test and then turning the head to the other side. The Epley has a high cure rate, especially if done repeatedly so after performing a few in the ED and teaching the patient how to do themselves, given them a patient information sheet with advice to perform several times a day until symptoms are no longer triggered by head movements.

If the Supine Roll test is positive for lateral canal BPPV, treat with the Gufoni manoeuvre (to learn see BPPV videos below).

BPPV Videos

The Emergency Procedures App online (also available in Apple and Android app stores for devices) has great videos demonstrating these tests/treatments:

- BPPV Posterior Canal

- Diagnosis: Dix Hallpike Test

- Treatment: Epley Manoeuvre

- BPPV Lateral Canal (aka Horizontal Canal)

- Diagnosis: Supine Roll Test

- Treatment: Gufoni Manoeuvre

Just scroll down and select the “Vertigo” tab to see them.

With the use of these excellent resources and practice, these manoeuvres are an easy addition to the emergency clinicians toolkit to produce the best diagnostic and therapeutic outcomes for these patients. For posterior canal BPPV, the Dix-Hallpike test and the Epley’s manoeuvre are very simple for clinicians to learn, perform and memorise and arguably should become a standard expected part of clinical training. For lateral canal BPPV, the Supine Roll test is even easier to perform. However the Gufoni manoevure treatment, while straight forward to perform, involves turning of the head in a direction that depends critically on the correct identification of the exact type of lateral canal BPPV diagnosed during the Supine Roll test (geotropic v apogeotropic and left v right ear). Experience suggests, a quick refresher review of the related lateral canal BPPV videos below, is usually sufficient to recall these specific details in order to correctly interpret findings and perform treatment when suspecting lateral canal BPPV, but if in doubt, referral to a vestibular trained physio can be invaluable.

BPPV patients should no longer be misdiagnosed and unnecessarily investigated for central causes and treated only with medications when there are clear diagnostic and treatment modalities available.

This video provides further discussion with examples of the characteristic nystagmus patterns seen during the different BPPV tests (Dix-Hallpike and Supine Roll).

[Back to Top]

Acute Vestibular Syndrome (AVS)

“A clinical syndrome lasting days to weeks and generally including features suggestive of new, ongoing vestibular system dysfunction (e.g. nausea and vomiting, nystagmus, and postural instability). In the ED they are symptomatic even when at rest.” [GRACE Quote]

GRACE 3 recommends the use of the HINTS+ Exam to safely confirm a peripheral cause without further imaging in patients with AVS who test “HINTS+ peripheral”.

See the HINTS+ Exam Masterclass, partner article for a detailed understanding of the HINTS+ exam, including the pathophysiology behind the tricky Head Impulse test, tips on how best to perform well and HINTS+ exam pitfalls.

If the patient has a HINTS+ peripheral result, this confirms a peripheral cause of their AVS. If they don’t, they generally require investigation for a central cause.

Critics, including Dr Peter Johns, are concerned with the loose definition of AVS provided in the guidelines with associated advice to use the HINTS+ exam in such patients. They argue this definition of AVS is too non-specific and that true AVS absolutely requires the presence of continuous spontaneous nystagmus at rest because this is a distinct clinically entity that is commonly caused by peripheral vestibular disease (usually vestibular neuritis) but can be caused by central causes such as posterior circulation stroke. The HINTS+ exam is a validated test to help distinguish between peripheral and central causes in true AVS (where spontaneous nystagmus is present) but has no proven utility where nystagmus is not present. Indeed while GRACE 3 uses a loose definition of AVS they do emphasise the use of HINTS+ testing in patients without nystagmus as a common potential diagnostic error (Figure 3 on Common Errors in the guideline).

Therefore for the purposes of this article, I will define AVS with spontaneous nystagmus as “true-AVS” and AVS without spontaneous nystagmus as “pseudo-AVS”.

Where spontaneous nystagmus is not seen, before considering this to be pseudo-AVS, the first step is to check if it has been suppressed by the patient visually fixing on a point. Try Dr Peter John’s simple “blank paper” trick, which can reveal spontaneous nystagmus by removing fixation suppression. Alternatively, if available, the more expensive Frenzel goggles can be used for the same purpose.

Pseudo-AVS represents a different clinical entity of persistent dizziness without spontaneous nystagmus which has a broader range of differentials including:

-

- Central causes – consider investigation especially if there is gait ataxia or any abnormality on a thorough neurological assessment. Note when patients have true-AVS, mild to moderate gait ataxia is entirely expected but in Pseudo-AVS this is unexplained so unless there is an alternative explanation (e.g. medical cause), any new gait ataxia should warrant investigation for a central cause such as cerebellar stroke. See “when to be concerned about gait ataxia in acutely dizzy patients” for more explanation.

- Is it an atypical presentation of a vestibular syndrome?

- Peripheral AVS – as almost all cases of peripheral AVS have spontaneous nystagmus, it would be an uncommon cause of Pseudo-AVS, though in a delayed presentation after days, nystagmus can be absent.

- t-EVS – a minority of patients with t-EVS such as BPPV do complain of the persistence of a mild continuous dizzy feeling without vestibular symptoms (nausea/vomiting, postural instability) that is separate to their triggered vestibular episodes so if the history is consistent with t-EVS other than a mild continuous dizziness consider and test for this as described in the t-EVS section

- s-EVS, especially on first episode, may resemble pseudo AVS and these differentials should be explored.

- Medical Cause

- Alternative missed medical causes at Step 2 should be re-considered and reassessed for.

Spontaneous Episodic Vestibular Syndrome (s-EVS)

Defined in the Figure 1 from GRACE 3 above, key features are that the symptoms are episodic but spontaneous onset, not triggered by head movement. It is the repeated nature of these transient episodes that helps make the diagnosis. First episode or longer duration episodes may be difficult to distinguish from AVS and if symptoms are continuously present in the ED, “one would approach as an AVS and the true episodic nature may only be apparent in retrospect” [GRACE 3 Quote]

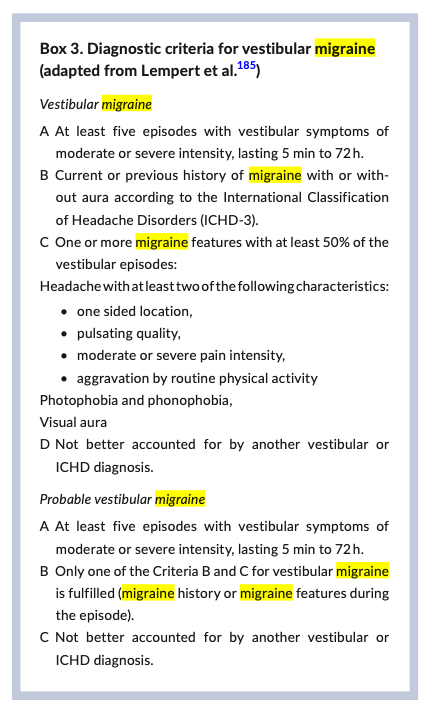

Of the 3 vestibular syndromes, s-EVS has been historically the least well recognised entity in the ED. As per Table 1 form GRACE 3 above, Vestibular migraine is a common yet poorly understood diagnosis of s-EVS in the ED, which is often missed. While episodes are typically short duration, about 1/4 of patients report a “duration of episodes between 4 hours and 3 days” [GRACE 3 Quote]. Box 3 from GRACE 3 provides diagnostic criteria.

Important serious diagnoses to consider for these transient episodes includes posterior circulation TIA, cardiac dysrhythmia and pulmonary emboli while Meniere’s disease is a less serious differential.

Nystagmus in the Acutely Dizzy Patient

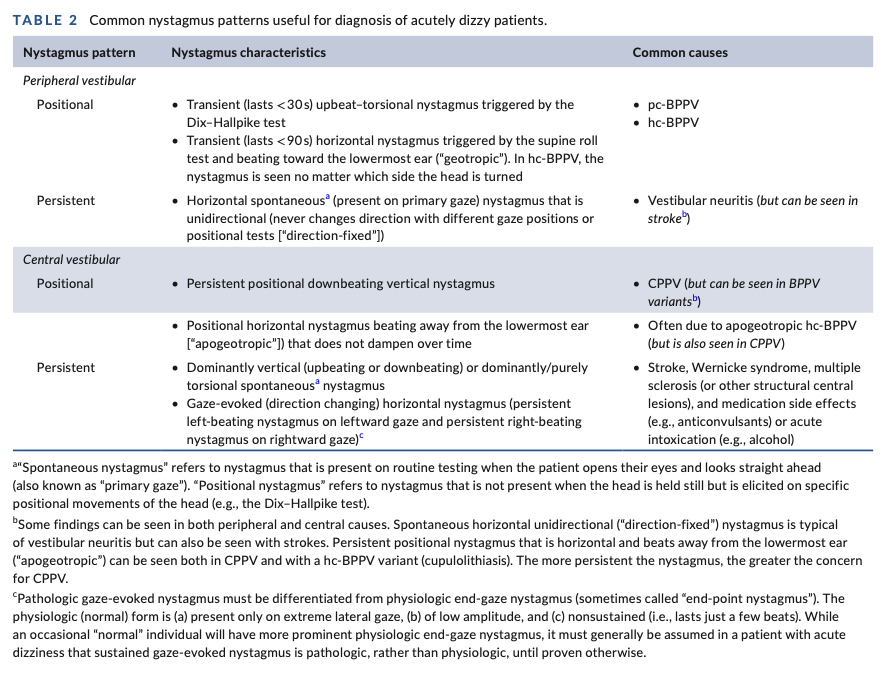

When seen in the acutely dizzy patient, nystagmus can be a very useful part of the examination to help determine the cause of the dizzy state particularly as part of the 3 vestibular syndromes. By contrast the absence of nystagmus largely excludes the peripheral causes of AVS as vestibular neuritis (common) and labrynthitis (uncommon) almost always have associated nystagmus in the first few days.

Nystagmus is observed during different states and tests:

- Spontaneous nystagmus at rest

- Gaze-evoked nystagmus during the HINTS+ exam, when differentiating central versus peripheral causes of Acute Vestibular Syndrome.

- Nystagmus during the diagnostic head movement tests for BPPV

Note that it is critical to interpret nystagmus based on the position of the head at the time. Features of nystagmus that occur when the head is still have entirely different diagnostic meaning compared to when the head has been deliberately moved during the tests for BPPV.

When examined at rest:

- Spontaneous nystagmus that is vertical (with or without torsional component) or purely torsional (rotatory) is strongly suggestive of a central neurological cause. Note that it is common for torsional nystagmus to be combined with horizontal nystagmus in peripheral causes of AVS so is only suggestive of a central cause if it is pure torsional nystagmus.

- Gazed-evoked nystagmus that is horizontal and unidirectional (fast beat always in one direction regardless of the direction of gaze) is typically seen in peripheral causes such as vestibular neuritis but its presence by itself does not exclude central causes.

- By contrast horizontal bidirectional gaze-evoked nystagmus (horizontal direction of the fast beat changes when looking to the left compared to when looking to the right) is indicative of a central cause.

- Critically, this must be differentiated from the non-pathological, end-gaze nystagmus seen at the extremes of lateral gaze and is of low amplitude and non-sustained (lasts usually for a few beats). “While an occasional “normal” individual will have more prominent physiologic end-gaze nystagmus, it must generally be assumed in a patient with acute dizziness that sustained gaze-evoked nystagmus is pathologic, rather than physiologic, until proven otherwise.” (GRACE guidelines quote).

- This video demonstrates end-gaze nystagmus, how to recognise it and stop it from occurring so it can be distinguished from bidirectional nystagmus.

BPPV Associated Nystagmus during Diagnostic Tests

- In patients with BPPV there should be no spontaneous nystagmus. It should only be evoked by head movement. In fact, if acutely dizzy patients have spontaneous nystagmus they likely have true-AVS and the tests for BPPV should not generally be performed as it may lead to misdiagnosis.

- The types of nystagmus that occur during these BPPV diagnostic tests are described in the t-EVS section.

Table 2 from GRACE 3 below summarises these nystagmus patterns.

Other Causes of Nystagmus

Acute nystagmus of various directions can be seen under the influence of a range of toxicological causes including anticonvulsants and recreational drugs such as ethanol, amphetamines, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, salicylates, SSRIs, lithium, dextromethorphan, MDMA, LSD and PCP (phencyclidine) . It is also commonly seen when using ketamine either recreationally or for analgesia and sedation within the ED.

Chronic nystagmus can be caused by a range of congenital and acquired conditions and is beyond the scope of this article.

[Back to Top]

When to be Concerned About Ataxia in Acutely Dizzy Patients

In the dizzy patient some degree of ataxia is common, especially in true Acute Vestibular Syndrome (AVS) where associated postural instability is part of the diagnostic criteria along with spontaneous nystagmus, dizziness (usually vertigo) and often nausea or vomiting.

Where AVS has a peripheral cause the postural instability is usually mild to moderate and with prompting, patients who have no pre-existing mobility problems are generally able to walk unaided. However severe forms of ataxia such as truncal ataxia or the inability to walk unaided, sufficiently raises the probability of a central cause that usually warrants investigation for such. Notably patients who are unable to walk unaided generally require admission regardless for safety during which such investigations can be performed. Patients with pre-existing mobility problems and the elderly can be a bit trickier as it doesn’t take much to prevent them from walking unaided. Consequently, they will likely be unfortunately overrepresented in this admitted and investigated group, though the elderly do have a higher incidence of central pathology.

The key feature of patients with true AVS with spontaneous nystagmus is that a peripheral cause fully explains the postural instability, so the ataxia is only concerning if it is severe (truncal ataxia or inability to walk unaided).

By contrast in patients with pseudo-AVS (constant dizziness at rest without spontaneous nystagmus) there is no automatic benign explanation for their postural instability. Consequently any gait ataxia is arguably concerning for a central cause if it cannot be explained by another medical condition (e.g. toxicology, hypotension, BSL/electrolyte imbalance etc).

Finally patients with triggered-Episodic Vestibular Syndrome (t-EVS) will often have expected instability when their symptoms are triggered. So patients with BPPV may have a bout of dizziness if they get up quickly but once they keep still for a while, they should be able to walk unaided if they keep their head still.

So in summary, concerning ataxia in the ED is any new onset ataxia that is unexpected or not otherwise explained by the presumed diagnosis such as:

- Severe ataxia in a patient with true-AVS (truncal ataxia or inability to walk unaided).

- Any gait ataxia in a patient with pseudo-AVS not otherwise explained by a medical condition

[Back to Top]

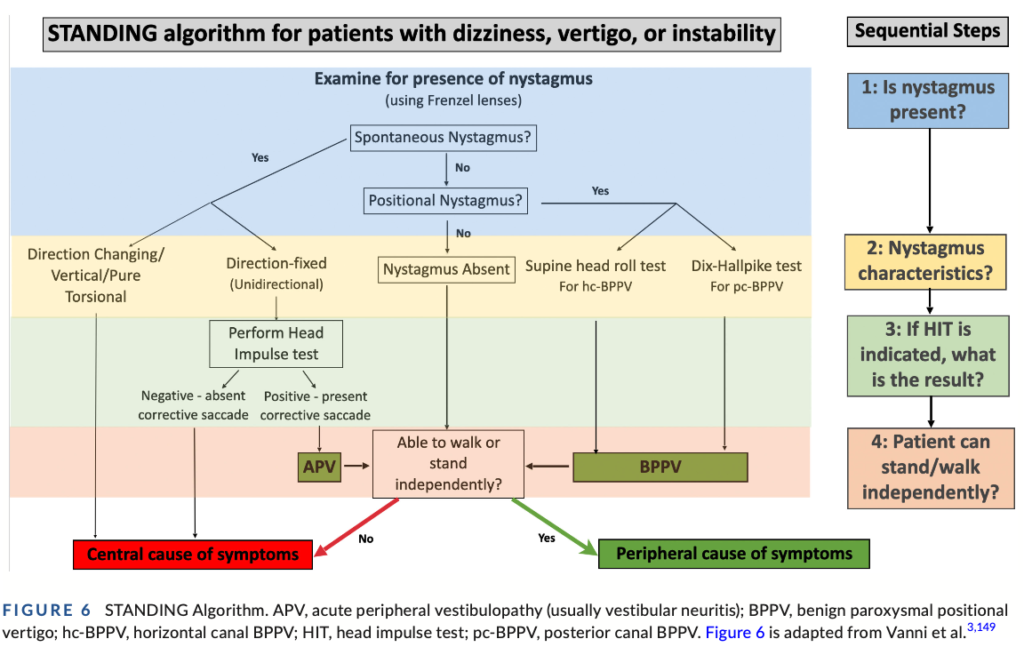

Standing Algorithm

As described above, nystagmus is such a critically important diagnostic tool when assessing patients with acute dizziness. Also discussed was that gait ataxia can be indicative of central causes. Consequently an alternative diagnostic algorithm that leads with the presence and type of nystagmus and ends with the ability to stand/walk has been proposed and validated known as the Standing Algorithm and it was discussed within GRACE 3.

The sensitivity for identifying a central cause of the dizziness (mostly strokes) ranged from 93.4% to 100% and the specificities from 71.8% to 94.3%. [GRACE quote].

The Standing Algorithm doesn’t include the test of skew or hearing from the HINTS+ exam. However these are very low sensitivity (but relatively specific tests) so failure to include them would miss few central diagnoses. However for completeness, one could easily append those 2 incredibly quick tests to the end of the algorithm which apparently on its own only takes < 3min to perform.

GRACE 3 Figure 6 shows the Standing Algorithm

[Back to Top]

Neuroimaging

GRACE 3 made a number of recommendations regarding imaging, generally downplaying the need and importance of neuroimaging. It is recommended to read their full 16 recommendations, several of which pertain to imaging.

Notably where a patient with t-EVS is diagnosed with typical posterior canal BPPV with characteristic nystagmus they recommend against routine imaging by CT, CTA, MRI or MRA.

Additionally in patients with true-AVS (with spontaneous nystagmus) and no neurological red flags on assessment, they recommend use of the HINTS+ exam (by a physician trained in its use) instead of imaging to distinguish between peripheral and central AVS; only imaging if peripheral AVS is not confirmed by HINTS+ (i.e. HINTS+ central or equivocal).

Where imaging is used for AVS they recommend against routine use of non-contrast CT or CTA to distinguish between central and peripheral causes as the accuracy of CT imaging of the posterior fossa is low in general and for stroke quite poor compared to MRI. If imaging required they recommend MRI (with DWI and MRA) but note that delayed MRI at 48h-72hrs can be more accurate.

“In adult ED patients with s-EVS, the writing committee believes that routine use of a detailed history and physical examination with emphasis on cranial nerves including visual fields, eye movements, limb coordination, and gait assessment helps to distinguish between central (TIA) and peripheral (vestibular migraine, Menière disease) diagnoses” [GRACE 3 Quote]

In summary, where the thorough assessment of a patient with a vestibular syndrome points to a clear peripheral cause, GRACE 3 does not recommend routine neuroimaging, but when a peripheral cause is not confirmed they generally recommend MRI/MRA.

Clinicians often, while awaiting MRI, start with a non contrast CT +/- CTA to exclude intracranial haemorrhage (ICH) but ICH is an extremely rare cause of isolated dizziness. If there are no other features on neurological assessment (step 1) to suggest acute ICH or arterial dissection, non-contrast CT or CTA imaging is an extremely low yield test in patients presenting with isolated dizziness. “Almost all ICH patients presenting with dizziness will have other clinical findings beyond isolated dizziness.” [GRACE 3 Quote]

[Back to Top]

Follow Up

The key aim when assessing acutely dizzy patients in the ED is to make the obvious diagnoses so they can be optimally managed while excluding the acute serious disorders. However some less obvious disorders may only become evident on subsequent medical review.

Patients will generally need follow up with their general practitioner in order to ensure expected improvement consistent with the presumed diagnosis and investigate or refer on if this does not occur. Causes of s-EVS in particular may also only become evident on serial review by medical practitioners when the episodes recur. Uncommonly a new diagnosis of a serious chronic disorder such as multiple sclerosis (accounting for <2% of patients with AVS) will also only become apparent on such serial medical review and subsequent investigation.

A hospital or community physio with vestibular training can also be useful practitioners to follow up patients with vestibular disorders or symptoms. They can provide diagnostic confirmation (and treatment if BPPV), may find alternate diagnoses in atypical cases and can provide vestibular rehabilitation therapy for patients with ongoing symptoms.

Specialist neurology referral may be required where non-acute neurological diagnoses or concerns remain whereas specialist ENT (Ear, Nose & Throat) f/up may be more appropriate for some cases of peripheral vestibular conditions.

Medical diagnoses (step 2 of the approach) should be referred to GP or specialists as indicated by diagnosis.

[Back to Top]

Resources & References

- GRACE 3 Guidelines 2023: Guidelines for Reasonable and Appropriate Care in the ED: Acute dizziness and vertigo in the emergency department

- Note there is an unfortunate recurring typo in these guidelines that I have confirmed with the lead author where the word “triggered” (as part of describing triggered Episodic Vestibular Syndrome) has been erroneously replaced with the word “transient”. This occurs in the pdf version of the article on pages 446 (description of Figure 2), 448 (heading for

TransientTriggered Episodic Vestibular Syndrome), 452 (description of Figure 3), 453 (description of Figure 4) and 454 (Box 2, Question 5). - Edited Version: To avoid confusion, for educational purposes I make available an edited version of the pdf here where the typo has been crossed out and corrected.

- Note there is an unfortunate recurring typo in these guidelines that I have confirmed with the lead author where the word “triggered” (as part of describing triggered Episodic Vestibular Syndrome) has been erroneously replaced with the word “transient”. This occurs in the pdf version of the article on pages 446 (description of Figure 2), 448 (heading for

- HINTS+ Exam Masterclass – How to Understand and Perform Perfectly (partner article on EDguidelines.com)

- Dr Peter John’s youtube channel of Dizziness and Vertigo assesssment and treatment videos

- Emergency Procedures App online (also available in iOS and Android app stores). Scroll down and select the Vertigo tab for quick access to key videos demonstrating:

- BPPV Posterior Canal

- Diagnosis: Dix Hallpike Test

- Treatment: Epley Manoeuvre

- BPPV Lateral Canal

- Diagnosis: Supine Roll Test

- Treatment: Gufoni Manoeuvre

- Acute Vestibular Syndrome (true-AVS, strict definition) – HINTS+ Exam

- BPPV Posterior Canal

- EMCRIT Podcasts

- Other References

- Edlow, J. A. (2018). “Diagnosing Patients With Acute-Onset Persistent Dizziness.” Ann Emerg Med 71(5): 625-631.

- Johns, P. and J. Quinn (2020). “Clinical diagnosis of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo and vestibular neuritis.” Cmaj 192(8): E182-e186.

- Wüthrich, M., et al. (2023). “Systematic review and meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of spontaneous nystagmus patterns in acute vestibular syndrome.” Frontiers in neurology 14: 1208902-1208902.

[Back to Top]