Quick Links

Assessment

Clinical Presentation

Summary:

- COVID-19 can present with a wide range of symptoms, but fever and/or dry cough are most common.

- Approximately half of COVID-19 patients may be afebrile on presentation so the presence of fever should not be relied upon when determining if patients are “at risk” of COVID-19.

- In regions where COVID-19 has high endemic prevalence, the typical presentation will be less useful to clinicians and COVID-19 may need to be considered in a wide range of clinical presentations either as a triggering/exacerbating factor or as an incidental finding.

Fever (88%), dry cough (67%) are most common. Other less common symptoms include fatigue (38%), sputum production (33%), shortness of breath (19%), headache 13%), myalgia or arthralgia (15%), chills (11%), nausea or vomiting (5%), diarrhoea (4%). (WHO China 2020) Fever is commonly absent on arrival to ED – in one cohort fever was present in only 44% of patients at presentation but developed in 89% after hospitalisation. (Guan et al, NEJM 2020). Consequently screening for fever or respiratory infections symptoms will be required in order to be sufficiently sensitive to detect potential cases as the presence of fever can not be relied upon at presentation.

Rhinitis/nasal congestion alone is uncommon with COVID-19 (about 5%) and is more likely in keeping with influenza/common cold viruses. However COVID-19 is not ruled out and whether you consider COVID-19 in such patients will depend on the current overall prevalence of disease in your population and local public health advice.

Mean incubation period is 5-6 days, with a very wide range from 1-14 days (WHO China 2020).

Disease is generally slow onset in terms of severity (unlike influenza) with a 1 week prodrome of myalgias, cough, low grade fevers gradually leading to more severe trouble breathing in the second week of illness.

80% have mild-moderate disease, 14% have severe disease and 6% have critical disease. Individuals at highest risk for severe disease and death include people aged over 60 years and those with underlying conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory disease and cancer.(WHO China 2020).

Examination, aside from vital signs, is generally non-specific and unlikely to enhance diagnostic accuracy substantially. Given their marginal additional value, the role of previously routine examinations such as chest auscultation and throat inspection that expose staff to risk of infection, within the context of a pandemic is unclear.

It has been noted that patients can present hypoxic without significant tachypnoea and that lung auscultation can be unremarkable despite significant chest xray findings.

In regions where COVID-19 has high endemic prevalence, the typical presentation will be less useful to clinicians and COVID-19 may need to be considered in a wide range of clinical presentations either as a triggering/exacerbating factor or as an incidental finding.

Investigations

For unwell patients being assessed in ED, investigations are aimed at

- Risk stratifying for COVID-19 versus alternate aetiology

- Determining severity

Bloods:

Summary: Leukopaenia, lymphopaenia, raised CRP and a low procalcitonin (if available) may be suggestive of COVID-19

- Full Blood Count

- Usually normal WBC with leukopaenia in about 1/3

- Lymphopaenia common in ⅓-⅔

- CRP

- >10 in 61% on admission (Guan et al, NEJM 2020) and appears to track disease severity and prognosis. In patients suffering with severe respiratory failure with a normal CRP level an alternative diagnosis should always be sought. (IPCC19)

- Procalcitonin

- In the same large cohort, 95% of patients measured <0.5 (Guan et al, NEJM 2020). Increased procalcitonin may therefore indicate alternate diagnosis (e.g. bacterial pneumonia) or in admitted patients, an increase from baseline may indicate bacterial superinfection.

- Other tests may be indicated as required for assessment of the patient’s clinical state and signs of organ failure – e.g Urea & Electrolytes, Liver Function Tests (LFTs). Liver enzymes are frequently elevated in the presence of COVID-19 infection.

Micro

-

- PCR for COVID-19 and respiratory pathogens from throat and nasal/nasopharyngeal swabs. Staff obtaining swabs should wear PPE appropriate for routine care unless the patient has fever with breathlessness and/or severe cough in which case PPE appropriate for AGPs is recommended (Aus DOH PPE non-inpatient)

- While the test has high specificity, the false negative rate is unknown but reports range from 20-40% and this can be seen both very early in the disease but also in patients presenting late with severe disease who are past the viral replication phase and are well into the inflammatory phase.

- A number of rapid turnaround, point of care test kits that detect IgM & IgG have recently been approved for use in Australia and the federal Public Health Laboratory Network has released a statement regarding their use. Due to the time taken for antibodies to be develop they are thought to be insensitive during the first week of illness although some kits claim as high as 97% sensitivity and 99% specificity after 5 days of infection.

- Blood cultures should be obtained as per usual indications.

- PCR for COVID-19 and respiratory pathogens from throat and nasal/nasopharyngeal swabs. Staff obtaining swabs should wear PPE appropriate for routine care unless the patient has fever with breathlessness and/or severe cough in which case PPE appropriate for AGPs is recommended (Aus DOH PPE non-inpatient)

Imaging:

Chest Xray

Consider chest xray (CXR) in most patients, particularly those being considered for admission. Well patients, fit for discharge, are unlikely to benefit from CXR.

If CXR is performed, it is recommended to perform portable CXR in ED to minimise risk of disease spread. (ACEM – Imaging)

CT

CT is the most sensitive test (though relatively non-specific). (Fang 2020, Ai 2019), so consider:

- If CXR negative, and high degree of suspicion of COVID-19 and there is clinical need to determine diagnosis urgently that will change management

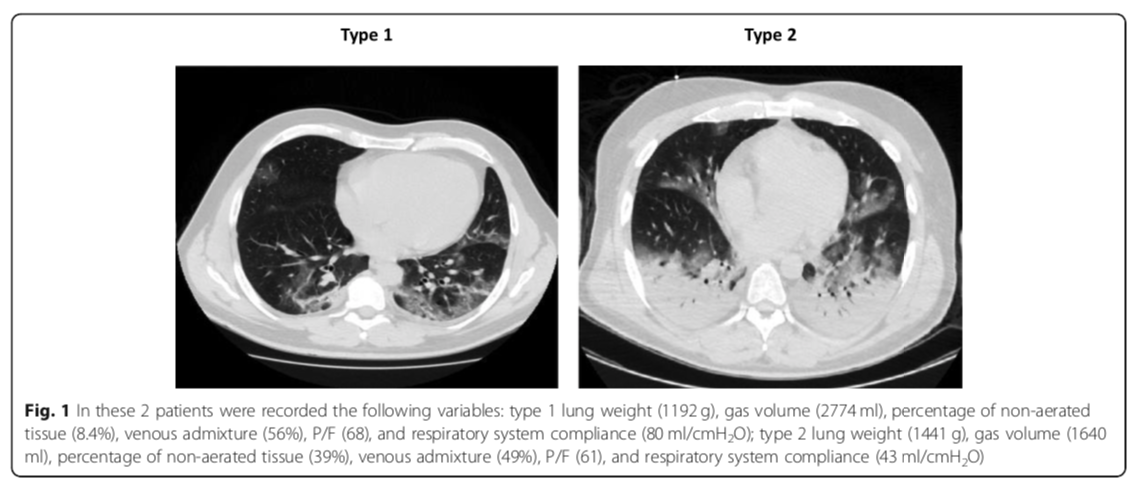

- e.g. as a discriminating tool to distinguish between L & H phenotypes (as suggested by Gattinoni 2020) to guide ventilator management in intubated patients (see Oxygenation Overview for more information)

However transport to CT can increase disease spread so should be used sparingly in selected cases. Patients transported to radiology will need all providers to wear PPE appropriate for routine patient care and the CT area will need appropriate cleaning post scan which could result in significant CT downtime.

COVID-19 suggestive changes on xray include include lobar/ multi-lobar / bilateral lung infiltrates/consolidation. (IPCC19) On CT changes include ground glass opacity and peripheral distribution of changes. However unilateral findings on CXR or CT occur in approximately 14-25% especially if mild or early disease.

Source: Gattinoni, L., et al. (2020). “COVID-19 pneumonia: ARDS or not?” Critical Care 24(1): 154.

L (Type 1) & H (Type 2) phenotypes explained in Oxygenation Overview section.

Ultrasound

There are promising reports of the utility of point of care ultrasound (POCUS) as a diagnostic modality of COVID-19 though widespread uniform guidelines for its use or evaluations of accuracy in this area are currently lacking. Disadvantages of POCUS include:

- Lack of uniform skills training in lung ultrasound across ED providers

- The length of time required in close proximity to the patient

- The extensive cleaning regime required of all ultrasound related parts post use in a suspect COVID-19 patient.

ACEM has stated they do not recommend CXR, CT or lung ultrasound to diagnose COVID-19 but do recommend its use for exclusion of other pathology from the differential diagnosis or to identify the cause of sudden deterioration in a patient. (ACEM – Imaging)

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.