Scope

This article provides education regarding pharmacological strategies used in sedation of the agitated patient in Emergency Departments (aka sedation for acute behavioural disturbance). Non-pharmacological strategies for managing agitated patients and the assessment and management of contributory pathology, should also always be employed, often before sedation is considered.; these topics are beyond the scope of this article.

For information regarding lawful rights to use restraint and sedation and when to consider the use of restrictive practices consult our Resources Regarding Restraint & Detention of Patients in Emergency Departments.

Please note that sedation of the agitated patient with acute behavioural disturbance is completely different to procedural sedation which is covered separately in our Approach to Procedural Sedation.

Disclaimer

In addition to our standard disclaimer, note that sedation of the agitated patient is a very high risk clinical process. This article is provided for educational purposes and may be a useful refresher for clinicians who are already competent in sedation or valuable learning for clinicians embarking on the path to attain competency. However by itself, this article does not provide such competency. Always consult local guidelines and policies and consult a senior clinician when seeking to apply information from this article. Additionally, the practice of clinicians with high expertise in sedation may reasonably differ from the approaches, agents, doses and timing recommended in this article.

Please note that the pharmacological properties and risks of the sedation agents are not discussed in detail – clinicians should consult alternative resources for full prescribing information about these medications before prescribing, including but not limited to, contraindications, precautions, adverse effects and interactions.

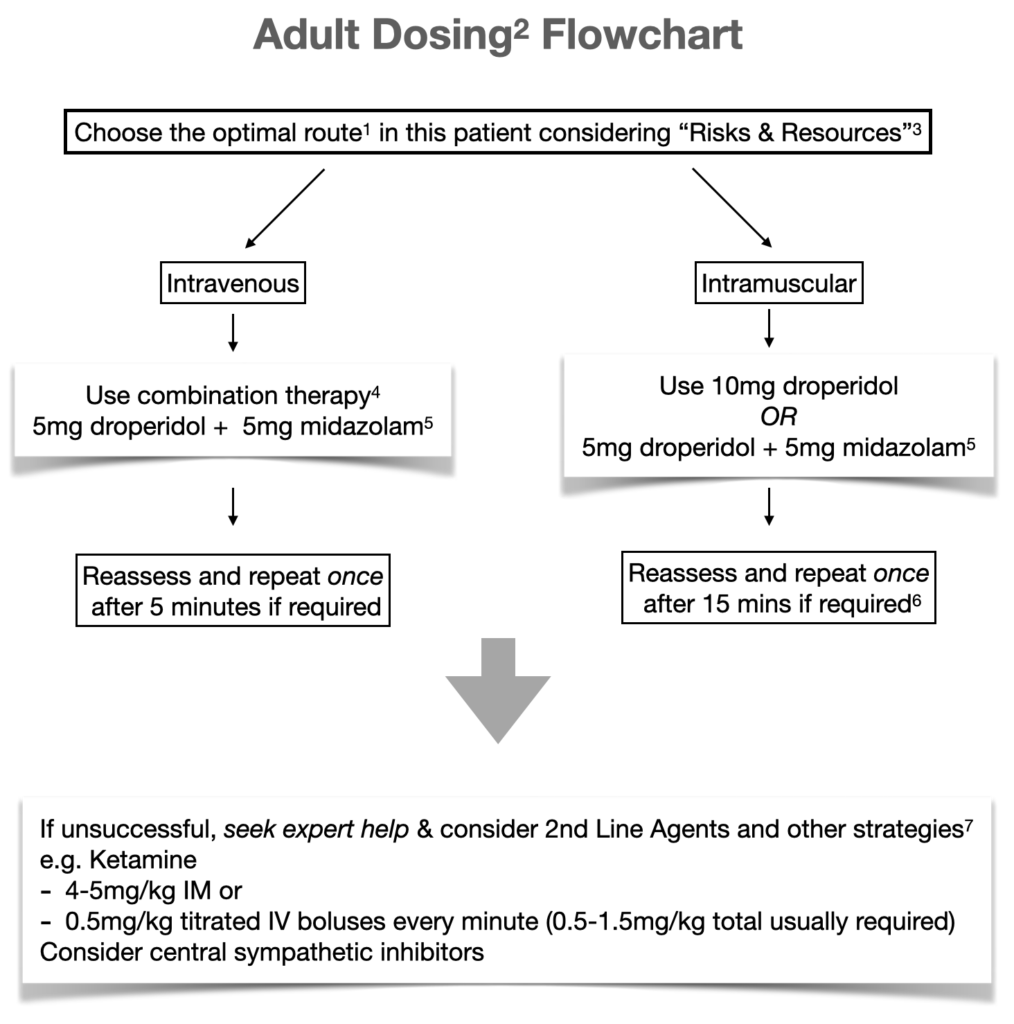

Flowchart for ED Initiation of Parenteral1 Sedation

Notes to Flowchart

1 – See “Choosing the Route of Sedation Delivery”

2 – Dose adjustments:

- Use half of doses shown for frail or elderly

- Consider lower doses in patients already partially sedated (e.g. due to co-ingestants/illness) or with lower levels of arousal

3 – See “Consider the Risks & Resources”

4 – See “Sedation Agent Choices”

5 – In lower resourced settings consider minimising benzodiazepine use (avoid or use lower doses)

6 – IV Access: if patient more settled after initial IM dose, consider IV access & delivery of additional required sedation IV

7 – See “Options for Patients Resistant to 1st Line Sedation Agents”; consider if resistant to:

- 20mg droperidol or

- The combination of 10mg droperidol and 10mg midazolam

8 – for Toxidromes – see “Sedation for Toxidromes”

- Titrated IV diazepam 5-10mg is preferred +/- droperidol

- Minimise antipsychotics if suspect anticholinergic syndrome

Consider the Risks & Resources

Consider the risks that require reduction

- Patient Self Harm

- Direct self harm or indirect harm through leaving the ED in a very unsafe state.

- Risk to Staff

- Sedation risks to patient from different drugs/routes of sedation given their clinical state, co-morbidities, likely co-ingestants

Balancing these risks will dictate the optimal speed of sedation required and partly inform the route and drugs used.

For example a highly agitated, physically violent, large individual may require rapid sedation to protect staff from imminent harm or to protect themselves from self-harm. This may favour the use of drugs or routes that provide rapid sedation e.g. robust doses of IV combination therapy.

By contrast for an elderly individual with co-morbidities who presents a lower risk to staff and is more easily able to be contained, a slower onset of sedation would be acceptable, and higher priority could be given to minimising the sedation-related risks to the patient e.g. lower doses of sedative medication spaced further apart.

Consider your resources available

Your resources may affect both the route and sedation agent choices.

Patients often require physical restraint in order to deliver the first or first few doses of parenteral sedation. The number of available restraint-trained staff and their skills may indicate what type of parenteral route to consider. For example if there are capable security guards or police available as part of the restraint team, and the patient’s upper limbs can be securely immobilised, the insertion of an IV cannula to titrate rapid onset sedation may be an optimal choice (see Choosing the Route of Sedation Delivery below). In settings with less available and capable restraint-trained staff, it may easier and safer to start with IM dosing.

In EDs with high sedation experience and critical care skills where clinicians can safely manage airway and breathing complications, benzodiazepines would usually be combined with anti-psychotics first line. Indeed, combination therapy, when appropriately dose-reduced and carefully titrated intravenously, provides the fastest and most effective sedation without any reduction in safety (see the Benefits of Combination Therapy section).

In settings with less sedation experience and critical care skills, there is a greater risk of inappropriate dosing and a reduced capacity to manage airway and breathing complications, particularly outside of closely monitored research trials where the applicable evidence has been generated. This may be particularly relevant where there is a lack of easy access to robust usable guidelines or timely senior assistance (in person or via telehealth). This may result in a preference for an approach that is more anti-psychotic “heavy”, avoiding or reducing the doses of benzodiazepines, especially if delivering IM dosing where the benefit of adding benzodiazepines to antipsychotics is less clear (as opposed to IV dosing where there is a demonstrated benefit of combination therapy). Theoretically, reducing benzodiazepine use may result in second line agents such as ketamine needing to be utilised earlier or more commonly.

In such lower resourced settings, seek expert help early.

Choosing the Route of Sedation Delivery

Choosing between the oral or parenteral route largely depends on the level of patient arousal and their cooperation with sedation medication.

The oral route is preferred for patients who are cooperative with taking oral sedation medication and whose assessment dictates slow onset of sedation is acceptable (see Consider Risks & Resources above). Parenteral sedation will generally be required in other patients.

Parenteral Sedation: IV (intravenous) versus IM (intra-muscular) Route

There is substantial controversy and practice variation regarding the choice of IV versus IM route. The choice of route requires nuance, tailored to the individual situation, considering several factors. The choice may be also be fluid as the clinician reacts to the circumstances and patient behaviour that presents itself but also as this evolves during sedation delivery and any associated restraint – an initial decision to use one route may require reassessment “on the fly”.

IV sedation:

- Provides faster sedation both because the medication is faster onset and because it can therefore be more rapidly titrated to the required dose at an acceptable sedation risk. This is because less time needs to elapse to observe most of the effect of that dose, before safely re-dosing.

- Faster sedation can minimise the risk to staff or patient self-harm in highly agitated violent patients.

- IV sedation can increase the sedation risk to the patient if the clinician is less experienced in IV sedation and chooses inappropriate doses/dose frequencies. By contrast, experienced hands can administer sedation with lower sedation risks through judicious rapid titration of appropriate doses.

- If an IV cannula is not already available, this requires a restraint team that has the skills and resources to immobilise a patient (especially upper limbs) for long enough in order to safely insert an IV cannula; or alternatively, a patient who decides to comply with IVC insertion once they realise restraint and sedation is inevitable.

- In addition if the patient is likely to be technically difficult to cannulate then the time taken to cannulate may outweigh any speed of onset benefits from the initial dose of IV sedation compared with the IM route.

- Where it is practically difficult to insert an IV cannula due to technical or patient compliance reasons, an initial IM dose followed by IV cannulation when the patient is more settled may be preferred.

- IV agents:

- IV combination therapy of droperidol plus midazolam provides the fastest and most effective sedation (see Benefits of Combination Therapy).

- IV droperidol and midazolam as sole agents are similarly effective at 10 minutes while midazolam may provide superior sedation at 5 minutes [Knott, 2006]. There is possibly increased increased airway and breathing risks with midazolam compared to droperidol as IV sole agents based on limited evidence and biological plausibility.

IM sedation:

- Is slower onset and therefore requires longer periods between re-dosing for an acceptable sedation risk.

- Requires less restraint to deliver the first dose – the degree of patient restraint and immobility required to deliver an IM dose safely is substantially less than to insert an IV cannula. This may place both the staff and patient at less restraint-related risk of harm in delivering that first dose of medication.

- (Note, there are some patients who cannot even be safely restrained well enough to deliver IM medication and will require alternative risk management strategies or resources called in to protect staff and/or the patient.)

- However, due to the slower onset, this may require a much longer period of physical restraint until the sedation takes effect. Longer periods of restraint increase restraint-related risk of harm to both the patient and staff.

- Highly agitated patients, if released from restraint before the sedation has taken effect, may seriously harm staff in attendance. This must be avoided and hence IM dosing may result in a lengthy physical restraint in such patients.

- By contrast, there are some patients, whose risk of violence to staff is assessed to be very low and whose primary indication for sedation was to reduce their risk of self-harm (directly harming themselves or indirect harm by leaving the ED in a very unsafe state). Such patients may be well managed with an IM dose requiring only a brief restraint and then can be released from restraint with staff stepping away from the patient, out of reach, to contain them from a distance. Staff can then remain on standby, continually reassessing their risk of violence and self harm and reactivate the team restraint only if required.

- Even if the IM route has been chosen for initial ED sedation, it is may be advisable to follow up with IV cannula insertion when the patient is more settled to provide the option of sedation delivery by IV route later and to manage sedation related complications (e.g. hypotension).

- IM Agents:

- IM Droperidol alone is preferred to IM Midazolam alone as it may result in less incidence of airway and breathing complications and less need for additional sedation. By the IM route, dose-reduced combination therapy (5mg droperidol + 5mg midazolam) performed similarly to 10mg IM droperidol [Isbister 2010].

Sedation Agent Choices

Introduction

All doses provided in this article are indicated for adults under 65 years of age. In elderly or frail, usually half of the recommended doses are used, especially initially. Lower doses may be used when sedation agents are combined or when the patient is already partially sedated by co-ingestion of sedating drugs (e.g. alcohol, benzodiazepines) or illness, or simply exhibits lower levels of arousal.

Dose or dose frequency ranges are provided because different doses are often suitable for different patients depending on their size, arousal or co-morbidities/co-ingestants but also because different resources and guidelines recommend different doses.

Antipsychotics and/or Benzodiazepines are generally used first line as sedation agents either alone or in combination. Some patients may require a specific agent not just for their sedation but also for the treatment of their underlying condition (e.g. antipsychotics for psychosis, diazepam for alcohol withdrawal or toxidromes).

The Benefits of Combination Therapy

Combination therapy can provide synergistic effects with regard to sedation.

With oral dosing the combination may provide a more effective sedation that can be more quick acting than sole agents, especially for patients with higher levels of arousal.

With parenteral dosing, the combination:

- Usually allows the use of lower doses of each agent compared with using each agent alone to achieve the same effective level of sedation.

- When used IV can provide faster and more effective sedation than using either an antipsychotic or benzodiazepine alone.

For example for a moderate to severely agitated patient: a widely used, evidence-based IV combination dose of droperidol and midazolam is the famous “5 and 5” i.e. 5mg droperidol and 5mg midazolam.

- This was demonstrated to provide quicker and more effective sedation compared to 10mg droperidol IV with similar adverse events [Taylor 2017].

- This provides faster and more effective sedation compared to titrated IV midazolam starting with 5mg IV [Chan 2013]

By contrast when administered IM, one small study showed the “5 and 5” combination provided similar sedation to 10mg droperidol alone or 10mg midazolam alone, but midazolam alone appeared to have a higher incidence of airway and breathing complications and greater need for additional sedation. [Isbister 2010]

Conclusion: IV combination therapy, at lower doses than would be used for solo agents, is likely the optimal solution in many situations, having considered your Risks & Resources and choice of delivery route. If administering IM, it is no better than droperidol alone and may be safer and more effective than midazolam alone.

Oral Agents

Benzodiazepines

- Lorazepam 1-2mg (max 6-8mg in 24hrs).

- Diazepam 5-20mg (max 60mg in 24hrs).

Can be repeated every 30-60min.

Antipsychotics

- Olanzapine is generally first line due to formulations that are more rapidly absorbed than tablets such as the wafer.

- 5-10mg (max 30mg in 24hrs)

- eTG states can repeat every 30min (though some sources suggest waiting 2 hours).

Parenteral Agents

Antipsychotics

- Droperidol is first line

- IV/IM 5-10mg (max 20mg in 24hrs)

- If sole agent, usually 10mg is given, whereas if combined with midazolam usually 5mg is given.

- Redosing:

- IV every 5-10min (a 5mg dose can be repeated every 5min, but a 10min interval may be more common and safer following 10mg dosing)

- IM every 15min

- Olanzapine is an alternative if droperidol can’t be used (e.g. allergy)

- 10mg IM (max 30mg in 24hrs)

- Redosing: eTG recommends repeat every 30min (though some sources suggest waiting 2 hours).

- IV use is not officially licensed in Australia but some research supports its IV use at similar doses. [Taylor, 2017]

Historical concerns regarding prolongation of QT by droperidol and the resultant risk of Torsades de Pointes seem to have been exaggerated. A prospective study of over 1000 patients, sedated with 10mg IM droperidol, once or twice (10-20mg total) for agitation, only identified 6 patients who developed prolonged QT and no patients developed Torsades. [Calver 2015]

Benzodiazepines

- Midazolam

- Most common choice due to rapid onset and ability to use both IV and IM

- IV: 5mg every 3-5 minutes

- IM 5-10mg every 15 minutes

- Ideally obtain IV access after 1st dose for subsequent carefully titrated dosing

- If 20mg cumulative delivered dose over time is insufficient – seek expert advice.

- Duration of action is often only 1-2 hours, so often is not the optimal choice when extended periods of sedation are required.

- Diazepam

- Can only be given parenterally IV (not IM), preferably through a decent sized vein to minimise stinging sensation

- 5-10mg IV doses every 5-10minutes.

- Preferred over midazolam when longer periods of sedation are required.

- So this may be used first line instead of midazolam if suitable IV line available and rapidity of onset not crucial.

- Alternatively it can be used for subsequent dosing after an effective initial sedation with midazolam, when the patient rouses and still requires extension of duration of sedation.

- It is first line in the provision of sedation during Toxidromes such as sympathomimetic, serotenergic and anticholinergic – see Sedation for Toxidromes section.

Options for Patients Resistant to 1st Line Sedation Agents

Occasionally some patients can be very difficult to either initially sedate or keep sedated effectively, despite significant combined antipsychotic and benzodiazepine delivery. Seek expert help regarding these patients and the use of the following medications. Note that while it is usually optimal to commence a rescue agent (below) at this point, balancing individual risks in a particular patient, an expert may occasionally recommend additional doses of antipsychotics or benzodiazepines beyond the 2 steps shown in the standard flowchart. This may be in preference to, or in addition to, the rescue agents below on a case by case basis.

Other Agents (“Rescue Therapy”)

- Ketamine

- IV

- Give 0.5mg/kg doses every 60 seconds titrated to effect

- 1-1.5mg/kg total dose may be needed if sole agent but less (0.5mg/kg) may be sufficient in some patients in combination with other sedatives.

- IM: 4-5mg/kg

- To maintain sedation in some patients, the initial ketamine IV or IM stat dosing may require follow up with a ketamine infusion commenced at 1mg/kg/hr and titrated to effect or side effects, using the minimum dose rate required.

- Safety

- Has relative safety compared with other sedation agents from an airway and breathing point of view (a rare risk of laryngospasm exists) because it creates a dissociative state rather than deep level of traditional sedation.

- However large IV doses (e.g 1-1.5mg/kg) given as rapid bolus can occasionally cause periods of apnoea – hence dosing recommendations above to use 0.5mg/kg aliquots.

- Can create behavioural problems, delirium and dysphoria on descent or emergence into/from the dissociative state. Such problems are less likely when the patient has already received sedation with midazolam or antipsychotics prior (demonstrated at least in the procedural sedation setting) [Akhlagi 2019]. For these reasons, ketamine is not usually used 1st line but is an excellent “rescue” option.

- IV

- Central sympathetic inhibitors (alpha 2 agonists)

- Provide sedation (and a degree of analgesia) via sympathetic inhibition.

- Some expert opinion suggests these agents may be of particular use in agitation due to certain toxidromes (e.g. sympathomimetic) and withdrawal states though there is little evidence examining this.

- These agents are often unavailable in EDs and may require sourcing from Intensive Care Units.

- Beware bradycardia, blood pressure instability (initial brief hypertension followed by prolonged hypotension), medication interactions (e.g. with beta blockers) and consider the patient’s physiologic need for preserved sympathetic drive (e.g. sepsis, shock states)

- Closely monitor HR and BP

- Clonidine

- Dose: 100mcg in 10ml saline given slowly IV over 5-10min; can repeat after 15min to a maximum of 200mg

- Oral dosing regimens suggest 50-200mcg QID

- Dexmedetomidine:

- Similar to clonidine with probably better sedation. Frequently used in ICUs for sedation, often in preference to other agents (such as benzodiazepines) due to observations of less associated delirium and relative preservation of respiratory effort, especially in the peri-extubation period and to help patients tolerate Non-Invasive Ventilation.

- Infusion: 0.2-1.0 mcg/kg/hr, starting at 0.4mcg/kg/hr and titrating to effect or side effects, using minimum dose rate required.

- While the official drug information includes a loading dose (1 mcg/kg over 10 minutes) numerous sources recommend omitting the loading dose as it is associated with a greater risk of cardiovascular complications.

Other Strategies

- Ensure you have optimised the use of non-pharmacological strategies (beyond the scope of this article).

- Ensure you have assessed, investigated and treated any primary or exacerbating causes of agitation.

- Treat concurrent contributory pathophysiology (e.g. hypoxia, hypercapnia, BSL/metabolic, hypotension, sepsis, CNS infections, seizure activity, toxicological intoxication/withdrawal etc)

- Observe for acute extrapyramidal side effects of antipsychotic sedatives delivered, such as dystonia and akathisia, which may masquerade as ongoing agitation. If suspected, consider treatment with benzatropine 1-2mg IV/IM.

- Treat pain

- Untreated pain may not be easily recognised in agitated patients and can contribute to their sedation-resistant agitation

- Aside from usual non-opioid agents, carefully titrated doses of IV opioids may have dramatic effects. If other sedatives such as benzodiazepines have been used, be careful and “go low and go slow” e.g. 2.5mg morphine or 25mcg fentanyl titrated doses and have naloxone available to reverse if needed.

- In some patients, where pain is suspected and where speed of sedation is not critical, it may be appropriate to trial analgesia first line as this may avoid or reduce the amount of sedation required.

- Bladder care:

- Urinary retention can commonly exacerbate agitation, especially in toxidromes such as anticholinergic syndrome

- A bladder scan, repeated every 4 hours is advisable in agitated and sedated patients along with the insertion of an indwelling urinary catheter as required.

Sedation for Toxidromes

Sedation is often required in toxidromes such as sympathomimetic, seroternergic and anticholinergic syndromes.

Benzodiazepines, usually titrated IV diazepam (5-10mg doses every 5-10min), are generally used first line because:

- The extended duration of action with slow offset is appropriate to the extended duration of toxidrome

- It co-targets the suppression of severe physiological autonomic excitation such as severe hypertension, tachycardia, hyperreflexia and clonus.

For these same reasons titrated IV diazepam is usually first line treatment for agitation due to toxicological withdrawal as well such as withdrawal associated with alcohol and benzodiazepine addiction.

Addition of an antipsychotic is required if physiological targets have been met and additional sedation is required or because agitation is so severe more rapid and effective sedation is required.

Antipsychotics are generally avoided if anticholinergic syndrome is suspected as the additional anticholinergic load can worse the clinical presentation and delirium though some sources do permit the use of droperidol to control agitation resistant to benzodiazapines, in cases of anticholinergic syndrome where the cause is not due to antipsychotic overdose (e.g. antihistamine overdose). Antipsychotics are contraindicated in suspected neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

Additionally, specific antidotes may be indicated in the treatment of particular toxidromes and drug poisonings to assist with agitation management – consult Toxicological resources and on-call advisory services (Poisons Information Centre national hotline 13 11 26 and/or local on-call Toxicologists)

Monitoring for the Sedated Patient

Monitoring will depend on the type and route of sedation delivered, patient specific concerns and co-morbidities and available resources and skill mix.

In general, in the ED it is essential to have:

- More intensive nursing ratios to observe sedated patients

- Continuous saturations

- Regular blood pressure monitoring

It can be desirable to additionally have:

- CO2 monitoring (usually but not exclusively via a nasal prong detector)

- Continuous cardiac monitoring (if available)

If the patient’s arousal changes and consciousness improves, reassess their decision-making capacity and risks that require reduction. See Resources Regarding Restraint and Detention of ED Patients for more information about this.

References

Guidelines

- eTG (electronic Therapeutic Guidelines, Australia): Pharmacological management for acute behavioural disturbance in adults (accessed 6/10/24)

- MIMS online drug resource (accessed 6/10/24)

- Hospital and Health Service Guidelines

- Fiona Stanley Hospital – Acute Severe Behavioural Disturbance (ASBD), Management in the Emergency Department

- NSW Health – Management of Patients with Acute Severe Behavioural Disturbance in Emergency Departments (2015)

- Royal Perth Hospital – Pharmaceutical Management of Acute Agitation and Arousal in Patients Under 65 (Nov 2021)

- Royal Perth Hospital – Pharmacological Management of Acute Agitation and Arousal in the Intensive Care Unit Clinical Guideline (May 2019)

- Safer Care Victoria – Caring for People Displaying Acute Behavioural Disturbance (2021)

- WA Country Health Service – Acute Behavioural Disturbance in Emergency Departments (May 24)

- Pre-hospital & Retrieval Guidelines

- The Acutely Agitated Patient in a Remote Location: Assessment & Management Guidelines – a consensus statement by Australian aeromedical retrieval services (Alice Springs Hospital Retrieval Services, medStar, CareFlight, Royal Flying Doctor Service), 2015

- St Johns Ambulance WA Clinical Practice Guidelines

- Disturbed & Abnormal Behaviour (Oct 2022)

-

-

- Droperidol (March 2023), Ketamine (Oct 2022).

- Queensland Ambulance Service Guidelines

-

-

-

- Clinical Practice Procedures: Behavioural Disturbances/Emergency sedation – acute behavioural disturbance (Sept 2022)

- Drug Therapy Protocols: Droperidol (Sept 2024), Midazolam (Sept 2022) and Ketamine (July 2022)

-

- Toxicology

- Austin Health Clinical Toxicology Guidelines – accessed last 2/11/24

- eTG (electronic Therapeutic Guidelines, Australia) – Toxicology Toxinology – accessed last 2/11/24

Studies

- Akhlaghi, N., et al. (2019). “Premedication With Midazolam or Haloperidol to Prevent Recovery Agitation in Adults Undergoing Procedural Sedation With Ketamine: A Randomized Double-Blind Clinical Trial.” Ann Emerg Med 73(5): 462-469.

- Calver, L., et al. (2015). “The Safety and Effectiveness of Droperidol for Sedation of Acute Behavioral Disturbance in the Emergency Department.” Ann Emerg Med 66(3): 230-238.e231.

- Knott, J. C., et al. (2006). “Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing Intravenous Midazolam and Droperidol for Sedation of the Acutely Agitated Patient in the Emergency Department.” Ann Emerg Med 47(1): 61-67.

-